This is an updated version of this post in which I try to explain the nuts-and-bolts of how to apply the 'Show, Don't Tell' principle to your fiction.I'll be covering topics in the following order:

I've split this topic into several parts because I think there's many levels of subtlety when it comes to 'showing' rather than 'telling'. I'll start with what I consider the most basic techniques and work my way up to the most sophisticated ones that I've managed to mash into my wee brain.

Preamble: Show, Don't Tell (Sept 14, 2009)

Technique 1: Dramatize the Scene (Sept 21, 2009)

Technique 2: Avoid the 'To Be' Construction (Sept 21, 2009)

Technique 3: Avoid Cliches, Choose Fresh Language (Sept 28, 2009)

Technique 4: Action, Not Words (Oct 5, 2009)

Technique 5: The Art of Implying Information (Oct 12, 2009)

Technique 5 of ‘Show, Don’t Tell’: The Art of Implying Information

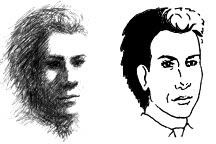

Which picture looks more lifelike to you?

Probably the one with grey in it, as opposed to the black-and-white one. When faced with ambiguity, your imagination fills in the blanks and infers what should be there. For example, the edges of the grey face aren’t well-defined on either side, yet your brain probably has no trouble believing they’re there.

A similar thing happens when you read the description of a scene in a novel. Not every detail of the scene can be mentioned, but if enough of them are, your imagination will fill in the blanks and give you a complete picture. Often, just one or two vividly-described images are enough to trigger this effect.

With insufficient description, a scene feels flat to the reader, but with too much, it becomes tedious to read. The ideal is for you, the writer, to limit yourself to relatively few sentences of description, but to work hard to ensure those sentences are vivid.

In choosing what to describe, try to pick a few slightly odd things that would stick out in a person’s memory. The commonplace parts of the scene are exactly what you can count on your reader’s imagination to fill in for you.

Here’s an example:

Light leaked between the shack’s planks and painted lines across a floor scabbed with blots of mildew.What material was the floor made out of? Was the room bright or dingy? Did the air smell musty? This example doesn’t say, but check the picture you have in your mind: did your brain fill in details beyond what was described?

Here's another example:

Sun had bleached the shack’s wood silver and laid a carpet of grass across its roof.What shape did the shack have? How many windows? Did you picture the sky behind it? The landscape in front of it? Again, your imagination probably added more to the picture than the text itself did.

Also, note it’s only implied in those two examples whether you’re inside or outside the shack. That’s another blank your brain filled in automatically.

As a writer, you want to strive to create a complete and vivid world using as few words as you can get away with. The way to do that is to strive to force the reader’s imagination to do half the work for you.

And that’s the heart of the ‘Show, Don’t Tell’ principle: it’s always the reader’s imagination that brings your story to life. Your words are merely a way to trigger it, and your task as a writer is to figure out how to.

There are lots of other places in your story where you can imply information, and thereby ‘show’ the reader things, rather than having the information come out in dialogue or exposition.

Emotional Information, or Subtext:

To expose what’s inside your character’s heart, I recommend using subtext. Let me define that: In acting, there is this idea of text and subtext. The text is the words in the script; the subtext is the meaning that the actors add to the text using vocal intonation, pacing and body language.

While the text gives a scene its structure, what makes it magnetic is the subtext. Think about how two actors portraying lovers can set the screen on fire by refraining from looking at one another. Remember how John Cleese in Monty Python’s Flying Circus could make one silent stare convey four different things in the space of about two seconds. Think about the body language that tells you when a character in a movie is lying. That’s subtext, and since it is ‘shown’, not ‘told’, it fascinates and engages the audience.

A novelist gets to add their own subtext, rather than relying on actors to do it, but I find it’s fruitful to consider how an actor would accomplish the job and then have your characters behave that way. A woman saying, “Where have you been?” while fiddling with her hair conveys something far different than a woman saying, “Where have you been?” while fiddling with a knife.

As always, it’s harder to ‘show’ something than to ‘tell’ it. It’s faster to have one character tell another that Bob is scared of women, but the reader will be far more interested in what’s going on inside Bob’s heart if they have to figure it out through seeing Bob consistently reacting to women in a way that implies fear.

Plot points and backstory can also be implied, rather than stated. I'll discuss these separately.

Plot Points:

If you describe a pattern of blood stains on the floor of a room, you’re forcing your reader to imagine that scene and to draw conclusions about what those spatters mean. This is ‘showing’, and it gives your story some ambiguity. Your reader can’t be sure they’re coming to the correct conclusion about what they’re imagining.

For this reason, ‘showing’ is a powerful tool when you want to set up a mystery. It leaves the reader slightly unsure until the moment you decide to definitively reveal your secrets.

Ambiguity has its problems, too. Some readers won’t be able to picture the scene accurately and will become confused or frustrated. This pulls them out of the story. If you’re worried this may happen, then ‘tell’ your readers the information instead. It’s better to be clear and dull than confusing but vivid.

Backstory:

Inserting backstory is notoriously difficult. Any lump of information delivered by exposition, whether via the writer informing the reader of facts or one character telling another those same facts, is what’s called an info-dump. Large info-dumps constitute ‘telling’ and thus are dull to read.

A better way to get the information across is to imply it as you go along. Have characters mention things in passing that, over the course of the entire novel, build up a complete picture of the backstory. Have the people in your book act in ways that are in keeping with whatever prior traumas they experienced, and then let the reader guess at what the traumas actually were.

Robert McKee in Story (a book on screenwriting that I heartily recommend to novelists also) has a suggestion for how to do this that I think is brilliant. He says the best way to use backstory is as ammunition: One character can use a shocking fact from the past to hurt, startle, or provoke another character, which will also be a delicious shock to the reader.

Finally:

Let me give you some evidence in support of my claim that implying information can create a more believable story than simply informing the audience of everything.

First, the confession: I am a ginormous dork. I went to see Star Wars, Episode II, Attack of the Clones, twice while it was in theatres.

If you saw that movie, you probably agree with me there were some very awesome bits (multi-Jedi lightsaber fights, whoo-hoo!) and some very terrible bits (Anakin’s wooing of Padme.)

The first time I went to see the movie, I probably saw the same version you did. The second time, however, I saw the IMAX version. As it happens, IMAX film projectors cannot physically fit the reel for any movie that is much longer than two hours.

In other words, the IMAX version had to be more tightly edited than the director’s cut.

And it was awesome. They chopped out Anakin’s retch-inducing speeches to Padme. They chopped that whole silly picnic scene. They shaved a few pretty-but-redundant scenes that had nothing to do with the young lovers. Suddenly, all the lousy bits were gone and what remained was one sleek, visually-glorious, kick-ass action movie.

The weird thing is that the romance between Anakin and Padme was more believable in the IMAX version. It was completely plausible that two good-looking young people living in each other’s pockets during a stressful time would fall for one another.

Why was this the case? Because the audience’s imagination filled in the blanks, and did so in a way that was more believable than George Lucas’ finely-detailed version of events. A few touches and meaningful looks were all the actors needed to communicate that Anakin and Padme were in love. The shenanigans with the picnic and the lusty speeches turned out to be utterly counter-productive to the story's intent.

In summary, acknowledge it is the reader’s imagination that brings your story to life, and that your job as a writer is to find ways to trigger it. Small, potent descriptions are your most economical way of doing this, because you can count on the reader’s mind to fill in the more commonplace details--provided you supply it a vivid enough ‘seed’ to work with.