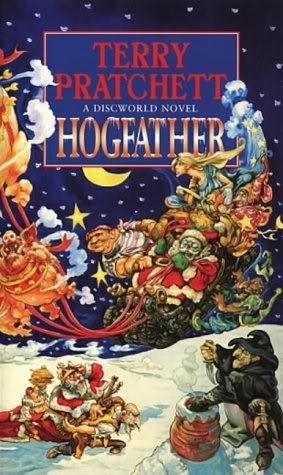

Excerpt of Hogfather by Terry PratchettThe problem with trying to analyze humour is as soon as you try to determine what makes something funny, it stops seeming funny.

There was no doubt that whoever had shut it wanted it to stay shut. Dozens of nails secured it to the door frame. Planks had been nailed right across. And finally it had, up until this morning, been hidden by a bookcase that had been put in front of it.

"And there's the sign, Ridcully," said the Dean. "You have read it, I assume. You know? The sign which says 'Do not, under any circumstances, open this door'?"

"Of course I've read it, " said Ridcully. "Why d'yer think I want it opened?"

"Er...why?" said the Lecturer in Recent Runes.

"To see why they wanted it shut, of course."†

†This exchange contains almost all you need to know about human civilization. At least, those bits of it that are now under the sea, fenced off or still smoking.

This is because surprise is an important part of humour. Humour consists of saying something that is recognizably true, but completely unexpected.

A joke's setup creates a scenario in the listener's mind.

An inebriated guest walks up to his host. "Mr. Hilcrombe, these lemons you've provided to flavour our drinks with are terrible!"The punchline twists the listener's assumptions in order to deliver an unexpected truth--an interpretation of that scenario that is valid, but a surprise.

"What? I haven't provided any lemons."

"Oh, good heavens! Then I must apologize, sir; I've just squeezed your canary into my martini."A simple knock-knock joke delivers a surprise interpretation of the answer to "Who's there?"

Knock, knock.The final answer is unexpected, but it's a valid interpretation of the setup.

Who's there?

Esther.

Esther who?

The Esther bunny.

Satire--which is what Mr. Pratchett specializes in--consists of saying deeply critical things about our world and ourselves. What makes satire funny is most people won't say these things--either out of politeness or because they haven't thought about the matter that deeply. Thus, to hear the sentiments expressed aloud is unexpected.

When someone laughs at a crude and nasty joke, it's often because they didn't expect the other person to say something so socially discouraged. When they laugh at fine satire, it's because they didn't expect to hear such a deep truth expressed so incisively and, perhaps, so mercilessly. Cruelty isn't what ties these two different kinds of humour together, however; surprise is.

In the above excerpt, the punchline is in the footnote, the setup is in the text. Mr. Pratchett shows the reader a depressingly familiar scenario, and after reading it, the reader likely feels--in a vague sort of way--exactly the sentiment Mr. Pratchett is about to express coldly and incisively: Forget the cat; curiosity kills humans with regularity.

When Mr. Pratchett actually expresses this criticism of humanity, it's funny because we instantly recognize the truth in his words, but they're still a surprise. People don't usually say things so bluntly.

Most humour consists of this duality of recognition and surprise, although visual jokes don't always fit neatly into the definition. For example, in a skit from Monty Python's Flying Circus, John Cleese and Eric Idle are standing on some grass beside a body of water. Eric Idle slaps John Cleese across the face with a fish. The audience giggles because this is a surprising thing to see. But what truth is being recognized?

There isn't one, but the humour also isn't enormously funny--yet. As the skit progresses, Mr. Idle continues to slap Mr. Cleese in the face with the fish, and his body language gradually shifts from frightened to confident to arrogant as he does so.

Mr. Cleese simply stands there, staring in outrage at Mr. Idle. Then, just as the skit is becoming tiresome and Mr. Idle is mincing up to yet again slap Mr. Cleese, Mr. Cleese whips out a HUGE fish he had hidden behind his leg and wallops Mr. Idle across the side of the head, knocking him into the water. And the skit ends.

Now, the joke's setup and punchline are obvious. The setup was a series of minor outrages perpetrated against a blameless person. The punchline was straight-up vengeance. Who can't relate to wanting to give someone a taste of their own medicine, with accrued interest?

We recognize instantly why Mr. Cleese whacked Mr. Idle with the massive halibut, and our surprise comes from the fact we didn't expect him to do it; the skit hadn't primed us for anything except passivity from him.

IN SUMMARY: What works in the above excerpt of Hogfather is the humour. The reader is shown a scenario under which lurks a deep truth about human nature. The punchline is provided when the author surprises the reader with that truth.

~~~~~~~

I'd like to do something different this week. Your thoughts (and dissent) in the comments section are always welcome, but for today's post, I'm assigning you homework:

1. Choose a piece of humour from any source (a book, a comedian's routine, a movie scene) and analyse why it's funny. What was the unexpected truth? Where did the surprise come from? Bonus points if you can do it for a piece of physical comedy; visual humour is often the hardest to decipher. Please post your analysis in the comments.

2. Using the concepts of truth-recognition and surprise, make up a brand new joke. Please post it in the comments section. (And if you require a straight man to pull off your joke, I'd be happy to act as your patsy!)

I look forward to seeing what you come up with!

And speaking of funny...